Communication is at the heart of everything we do in school, and perhaps particularly so at a school where bilingualism and multiculturalism are at the forefront of our identity. Whether we are engaging in everyday conversations, solving disputes, standing up for our beliefs, or telling our stories, our language is who we are and how we connect. It is thus invaluable for our students (and all members of our community) to learn to communicate with intention.

When communication is mindful and intentional, we can bring curiosity, kindness, and compassion to every interaction. Modeling and engaging in mindful and compassionate communication with our children, whether as teachers or parents, gives them invaluable tools for life. Among the many benefits of learning compassionate communication practices include developing the language to deal with interpersonal conflicts, methods for combatting communication anxiety (particularly in a bilingual setting), the ability to speak one’s truth authentically, and to listen to others empathically.

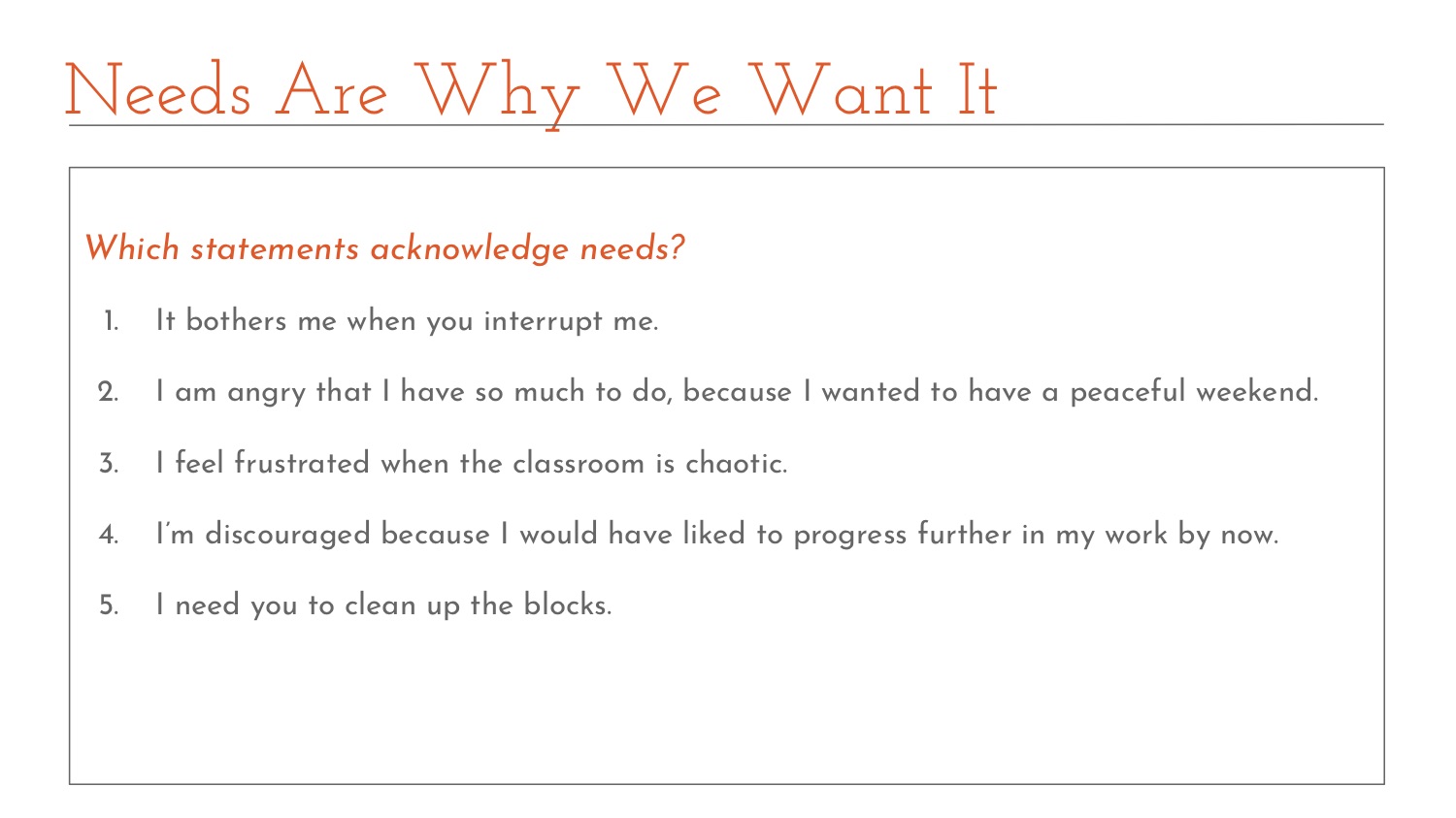

The following are some practices for mindful communication, based on the teachings of Oren Jay Sofer at Mindful Schools, an organization through which many Lycée faculty members have been trained in mindfulness for educators. Mindful School’s communication methods are inspired by the principles of Nonviolent Communication (NVC), a conflict resolution process and communication practice developed by psychologist Marshall Rosenberg beginning in the 1960s (Sofer, 2018). The guiding principle of NVC is that all human beings have the capacity for compassion, and violence or behavior that is harmful to others in any way is the result of not recognizing effective strategies for meeting universal human needs.

Presence: Embody it

Communicating mindfully depends on our ability to be truly present in our interactions. Amy Cuddy, a researcher who wrote a book on the subject called Presence (Cuddy, 2015), defines it as “the state of being attuned to and able to comfortably express our true thoughts, feelings, values and potential.” This concept is key to effective communication.

Presence is often missing in our daily interactions, as we are increasingly busy and distracted, whether by a list of things to do in our head, or a phone in our hand. This distraction can cause interactions and reactions that preclude empathy or true understanding. Mindful Communication trainer Oren Jay Sofer (2018) asserts that when teachers teach from a place of true presence it helps to regulate their students’ developing nervous systems.

We can transmit our internal state through body language, posture, facial expression and our voice. Though we are innately wired to be present, as an attentive awareness of our surroundings enables us to survive, we go through what Sofer (2018) refers to as “unconscious communication training,” where the habits we acquire from our family or culture undoes this innate presence. Fortunately, there are ways to cultivate the presence we need to give and receive fully in conversation and communication, using mindfulness practices.

We can transmit our internal state through body language, posture, facial expression and our voice. Though we are innately wired to be present, as an attentive awareness of our surroundings enables us to survive, we go through what Sofer (2018) refers to as “unconscious communication training,” where the habits we acquire from our family or culture undoes this innate presence. Fortunately, there are ways to cultivate the presence we need to give and receive fully in conversation and communication, using mindfulness practices.

The following are four techniques for grounding attention in the body, to make for a truly “embodied” presence that we can bring to our daily communication. It is helpful to practice these mindful skills (choose one or two that feel most natural for you) first on your own, and let them become habitual. You can then use them when communicating, first in “low-stakes” situations like everyday conversations, and then in more challenging situations.

-

- Feel gravity: The weight of the body the brings us in and down. While standing, notice this weight and how, even when you stand tall with good posture, you can feel the downward pull of gravity.

- Feel the center-line: Become aware of your spinal axis or the upright core of body. Try to visualize the vertical line down your body, either in the back or front.

- Feel the breath: The foundation of mindfulness practice, become aware of your breath. Notice it coming in and out, its length and its depth.

- Feel the hands or feet: Try to feel either your hands or your feet (without actually touching them). It is a great mindfulness exercise to do a feeling scan of all parts of the body, but for this quick practice, just choose the hands or feet, are the touchstones of direct sensation (Sofer, 2018) and thus the easiest to feel through sensing them.

Bringing one or two of these tools consistently to conversation has a true effect on feelings of groundedness and presence. Both adults and children can benefit from these mindful practices and their use in communicating.

Intention: Come from curiosity and care

Another principle of mindful communication is to come from curiosity and care, which builds connection and relationship (Sofer, 2018). In mindfulness practice, this principle is akin to setting a particular type of intention, which in the case of communication, would be a purpose for how and why we want to communicate. The motivation behind words can powerfully affect a dialogue, causing the speaker to rely on old habits in times of stress or challenge, causing argument, blame, defensiveness, avoidance or acquiescence, all of which inhibit true compassionate communication (Rosenberg, 2015). Bringing an intention to understand when communicating necessitates an outlook of curiosity and care, which builds a sense of sense of trust and strengthens the relationship.

As a teacher, and particularly one of young students, I find this sentiment profoundly important. If we can greet everything our students say, and do with curiosity and care, we can help them through challenges. This is ultimately our responsibility as teachers and parents. When a baby cries, we listen to the cry to try to figure out what the baby needs. We come from curiosity and care, knowing that this behavior, crying, is how the baby communicates.

As a teacher, and particularly one of young students, I find this sentiment profoundly important. If we can greet everything our students say, and do with curiosity and care, we can help them through challenges. This is ultimately our responsibility as teachers and parents. When a baby cries, we listen to the cry to try to figure out what the baby needs. We come from curiosity and care, knowing that this behavior, crying, is how the baby communicates.

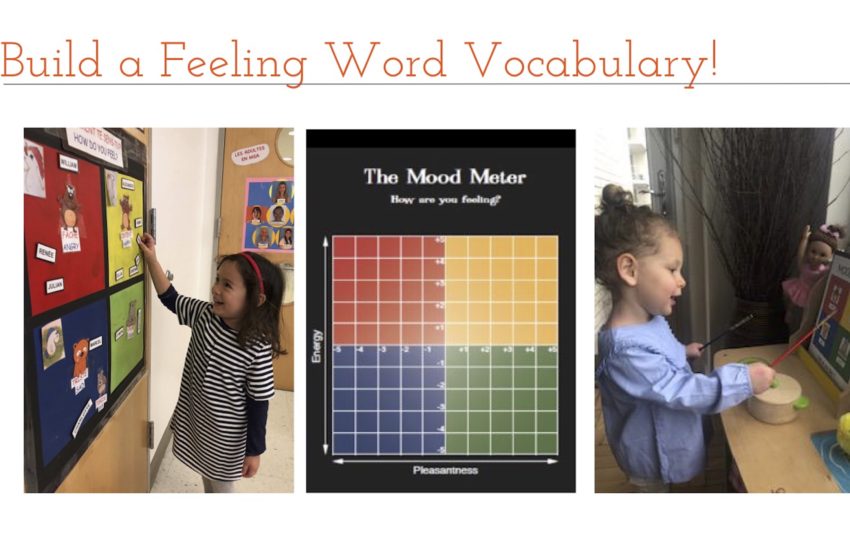

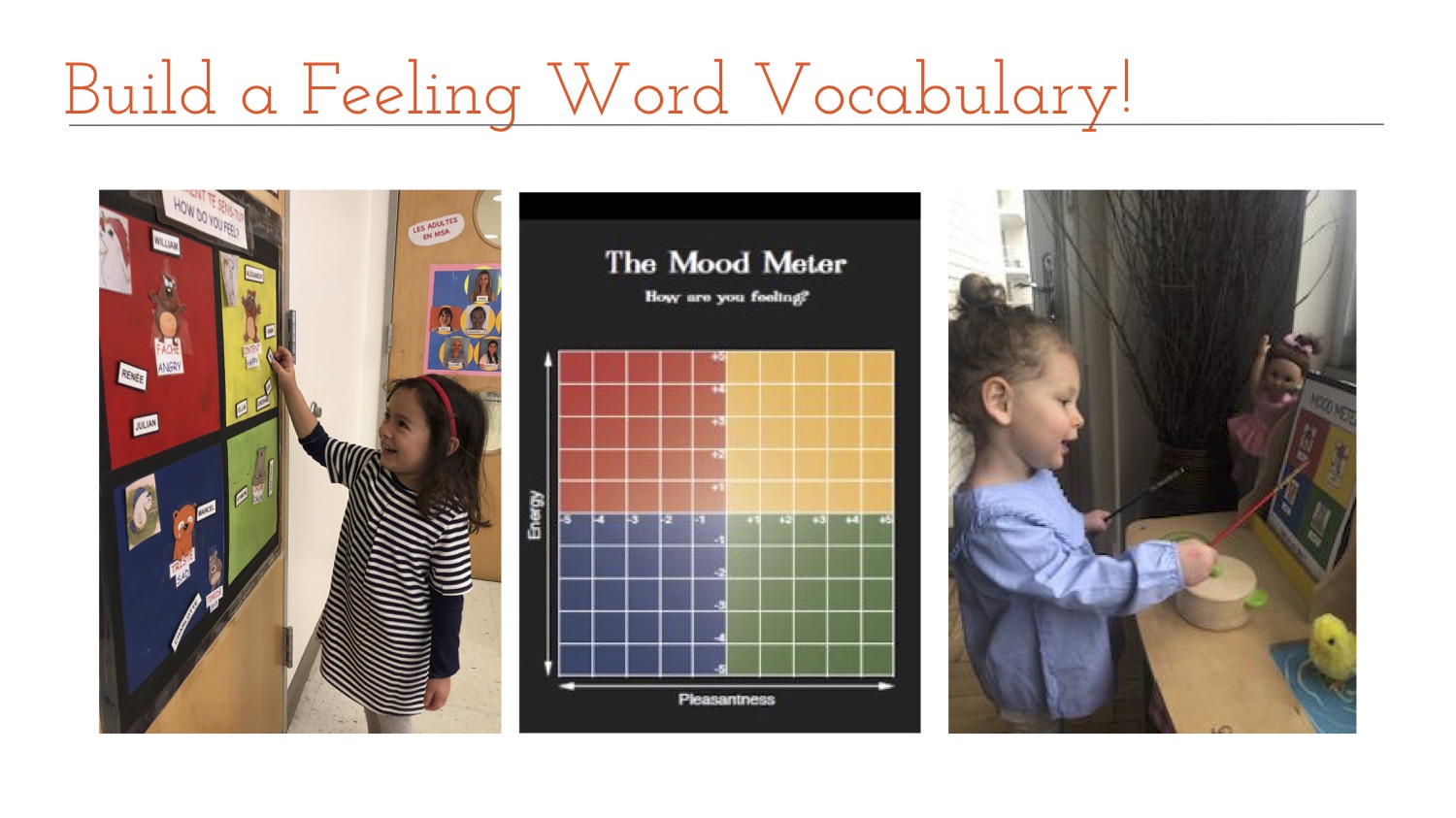

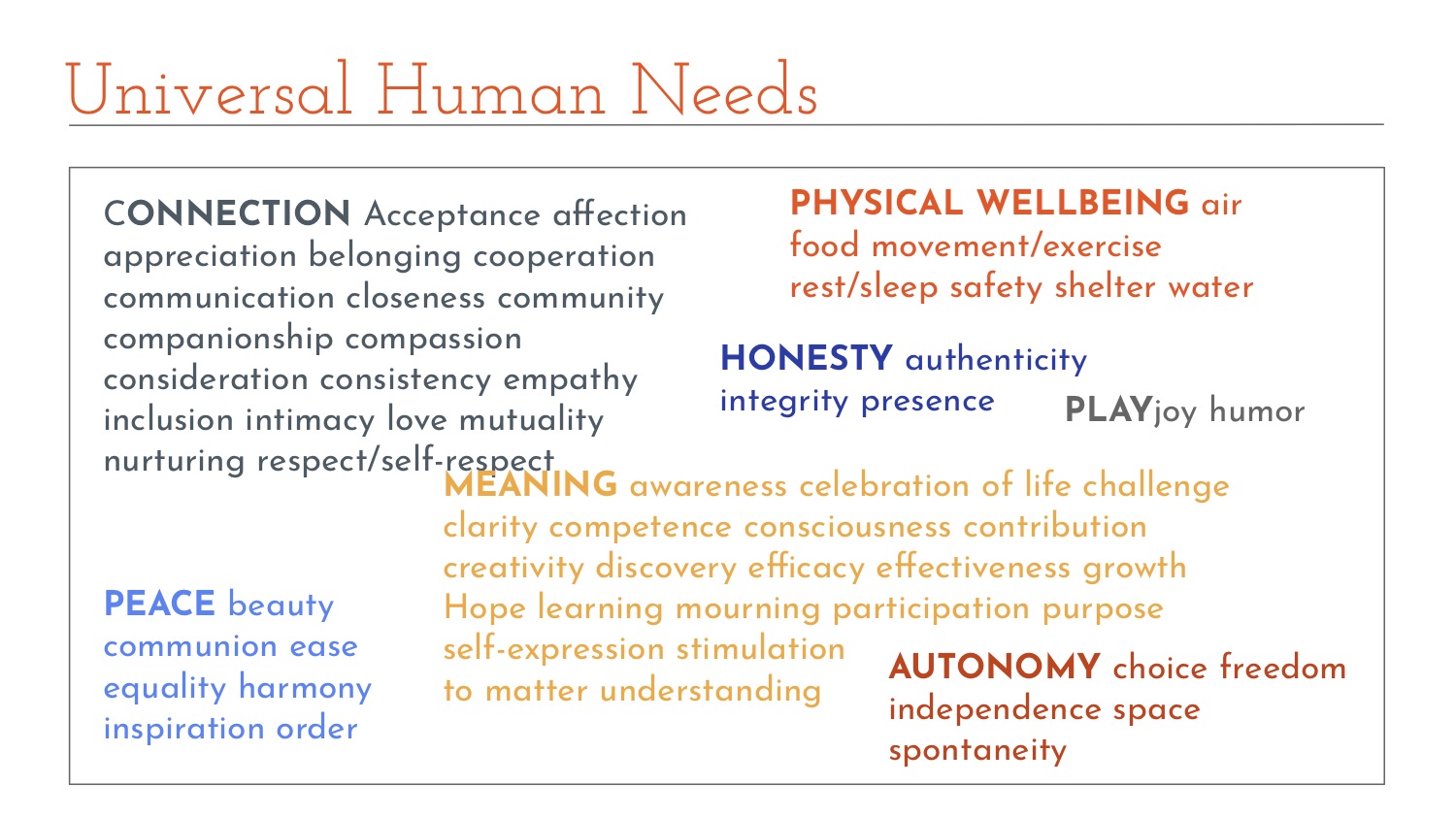

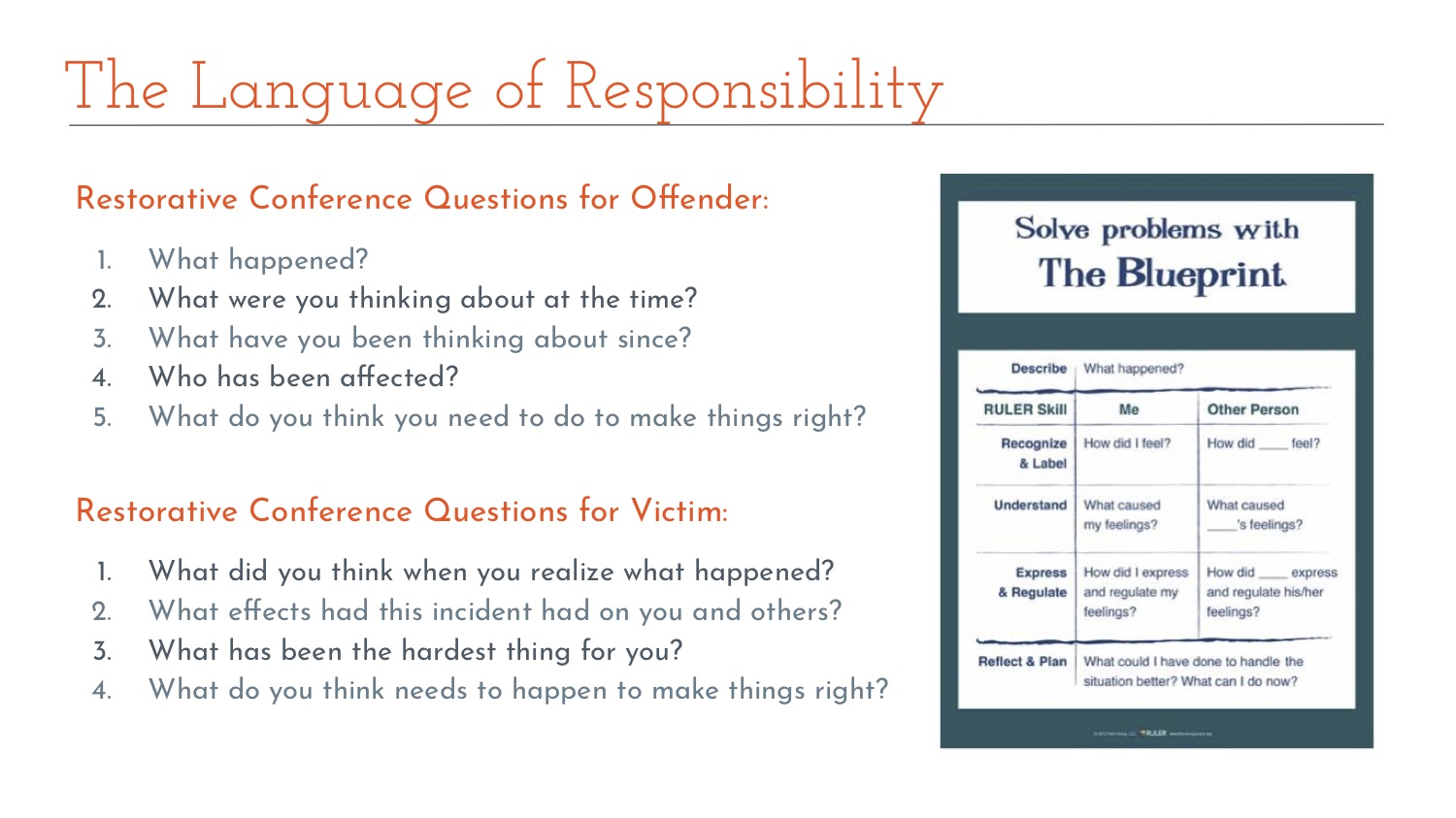

As Conscious Discipline founder Dr. Becky Bailey states: “All behavior is a form of communication. We acknowledge and act on this belief with babies. The challenge is holding onto this truth as the child matures.” Children are often reprimanded for “bad” behaviors, when in fact the behavior is really the communication of an unmet need. By coming from an intention of curiosity and care, by getting genuinely curious about their experience, we can set about discerning the children’s needs. This is where the work comes in of using Social and Emotional Learning practices, such as those of the RULER Approach, to develop the skills and strategies children and adults need to manage the emotions that come with unmet needs effectively. When we approach all of our parenting, teaching and communicating practices mindfully, this work becomes natural and even more intentional.

*

Further recommended reading:

Cuddy, A. (2015). Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges. New York, NY: Little Brown and Company.

Rosenberg, M.B. (2015). Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. Encinitas, CA: Puddle Dancer Press.

Sofer, O.J. (2018). Say What You Mean: A Mindful Approach to Nonviolent Communication. Boulder CO: Shambhala Publications.

About the Author :

Currently an English teacher in the Petite Section, Anne Morrison has taught different preschool levels at the Lycée Français since 2008, where she has also given many Social and Emotional Learning workshops for both teachers and parents. She also works with Yale University’s Center for Emotional Intelligence, for which she has developed SEL curriculum and trained teachers and administrators from around the world in the RULER Approach. This summer, Anne received a Research Fellowship from the Lycée to examine mindful communication and discipline practices that promote student and faculty well-being and social justice.