I’m sure you heard that one : Cervantes and Shakespeare died on the same day, April 23, 1616. Isn’t that neat ? The two famous writers, arguably the best poets of their time, relinquishing their last breath at about the same time, a few miles apart. This fun fact surely is worthy of a bottle cap[1] but the author of Don Quijote never had that privilege. The Bard did, of course, maybe because he was also born on April 23[2].

This being said, if we want to be more precise, we should say that Miguel and William died on the same date, but not on the same day. How is that even possible ? To understand it we need to go back to ancient times, Ancient Rome to be exact, and try to understand how “our”[3] calendar has evolved. For everything the Romans brought to our civilization, there is one domain where their contributions have been very poor, if not completely inexistant. I’m talking about mathematics of course, and abstract science in general. When you think about Pythagoras, Archimedes, Euclid and all the Greek scientists and philosophers who have marked our occidental way of thinking you may wonder why you can’t find one single Roman mathematician or scientist. Now I know some of you are thinking : What about Galen, the Roman physician who created modern medicine ? Well, first Galen was born in Turkey, of Greek origins, and then you have to admit medicine is more a practical science. Yes they built nice bridges and roads but as someone once summed it up nicely “The only thing the Romans brought to the world of mathematics is the death of Archimedes[4].”

The Egyptian Calendar, 4000 BC.

It is no wonder then that when Romulus supposedly put together the first Roman calendar, sometime around 750 BCE[5], he gave it only 10 months for a total of 304 days[6]. As a comparison, other civilizations such as the Egyptian or the Babylonian already had a 365 days calendar in place for many centuries at the time. It seems the Romans knew there ought to be more than 304 days but for some reason they left more than 50 “winter days” unregulated, unmonthed if you allow me that neologism. This was not unheard either. The Egyptian calendar had 12 months of 30 days plus 5 days at the end of year (the so-called epagomenal days) which were dedicated to the gods. Five extra days is fine if it keeps all the months with the same number of days, but 50 looks like sloppy mathematics. Then if you consider the names of the months (Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius, Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December) it looks as if Romulus found inspiration for four of them, such as Martius from Mars the god of war, but then got lazy and simply called them #5, #6 etc…[7] If you think about it, that’s the equivalent of Walt Disney naming the Seven Dwarves Doc, Grumpy, Happy, Sleepy, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh[8]. And if you’re thinking “Hey! Walt Disney didn’t write Snow White, the Grimm Brothers did.” you are of course absolutely right, except that they didn’t give names to the dwarves.

The sun gives the day and the year ; the moon gives the month

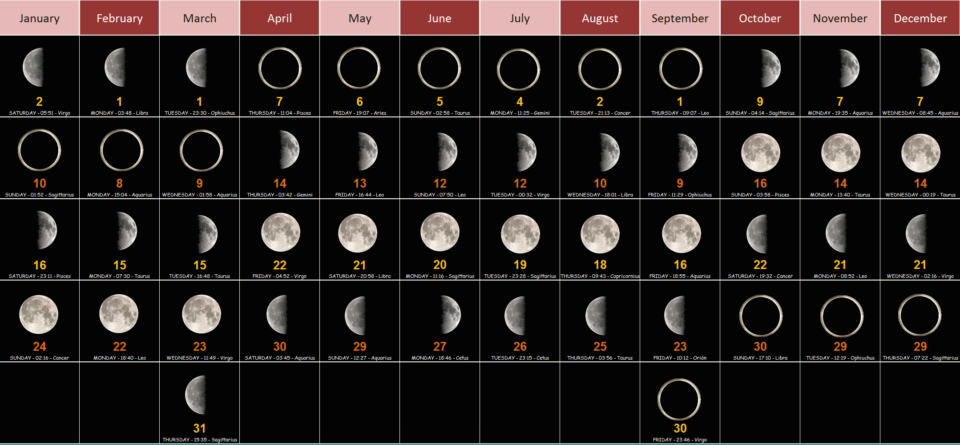

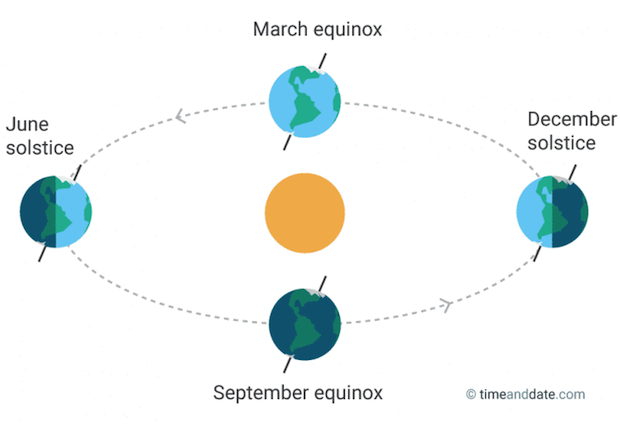

But enough with that. There’s no use in making fun of someone who may not even have existed. The next step in the history of the Roman calendar comes a few years later when, according to historians, Numa, the second king of Rome, decides to add the months of February and January (in that order, with 28 days each) and also reduces the six 30 days months to 29. That makes a total of 354 days. The difference with 365 is actually the difference between a lunar and a solar calendar and to explain this we need to understand how the passing of time can be measured on Earth. Basically, the sun gives the day and the year while the moon gives the month. For early astronomers, it was fairly easy to observe the changes of the moon and calculate that a lunation (the period of time between two new moons) was a bit more than 29.5 days. It took longer observations of the sun travelling in the starry night to discover that a year was about 365 days long. The combination of these two numbers justifies the division in 12 months and the difference of 11 days between 12 lunar months (12×29.5=354) and a solar year[9].

The 4 lunar phases for the year 2016 and for northern observers. For each phase: day number of the month, day of the week, phase hour (U.T.) and the constellation where is located the moon at that time (credit: Fernando de Gorocica).

So if you live on Earth and want to create your own calendar, you are pretty much limited by these two numbers. As a comparison, a Martian year has about 669 Martian days and because Mars has two moons, Phobos and Deimos, with respective lunations of 11 hours and about 3 days, one can only wonder what kind of calendar an observer would come up with. But back to Earth. Let’s assume you choose the lunar calendar. If you alternate 6 months of 30 days with 6 months of 29 days you’ll follow the moon closely but then the discrepancy of 11 days with the sun means that your seasons will be off pretty fast. After only 3 years you will be one month ahead and this means you will have no way to adequatly associate warm or cold weather to a particular month. Yes, I know, those of you who spent the December break in New York and enjoyed 70 degrees weather on christmas eve might say we are no better today but, as all good scientists know, “same effect” doesn’t mean “same cause”. It is certainly not my intention to include a lengthy digression on Global Warming here but when you learn that at some point during December it was warmer in the North Pole than in Boston you might think that even the most reticent people who keep fooling themselves by calling it “Climate change” should instead start calling it “Global Warning”.

Ramadan and Muslim Calendar

As you know, the traditional division in seasons was of course guided by natural observations such as the different cycles of life on Earth which obviously are related to how much sunlight a particular spot on our planet is receiving. It helps farmers to know when it’s time for sowing and when it’s time for harvest but if you don’t really care that Spring starts in December you don’t have to do anything about these 11 days and you can let your equinoxes and solstices travel along. A modern example of this is the Muslim Calendar and it explains why the Ramadan (the 9th month) doesn’t always correspond to the same month of the Western Calendar.

On the other hand, you could be more interested in keeping the seasons in orderly fashion, whatever your reasons. It is possible that an important and recurring natural event defines your year as the flood of the Nile did for the Egyptians and it explains why they came up with three seasons : Inundation, Growth and Harvest. Or maybe you have an excessive infatuation for the sun (again the Egyptians but also the Aztecs and many other civilizations) and then you will need to get closer to that 365 mark. There are different ways to do so depending on how much you want to mess with the moon. One convenient solution is to add an extra month once in a while. Records indicate that this “intercalation” was already used by the Sumerians as early as 2400 BCE and consisted in roughly delaying the start of the year if the crops were not ready to harvest. The technique (which was also introduced by Numa in the Roman Calendar) was later refined by the Babylonians and became what Europeans call a “metonic cycle” after Meton of Athens brought it to the Greeks in the 5th century BCE. It worked on a 19 year long cycle (about 6940 days) during which 7 years had 13 months instead of 12 thus giving a total of 235 months[10]. These extra apparitions of our satellite during a particular year are called “blue moons” and the fact that they appear only every 2 or 3 years explain the saying “once in a blue moon”. This type of calendars is still in use today. An example is the Hebrew Calendar which follows a metonic cycle and inserts an extra month to ensure that Passover happens in Spring[11].

Ides of March, Greek Calends

As you see, “luni-solar” can be complicated and you may decide to forget about the moon and have 30 days in each month just like the Egyptians. In that case you may go all the way and add the 5 remaining days to some months arbitrarily. This means that it is now the time to give back to Caesar what belongs to Caesar !! After he returned from his Egyptian campaign, Julius Caesar decided to reform the Roman calendar with the help of the Greek astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria. First, Caesar decided that the first day of the year 45 BCE should be the first day of January instead of the first day of March. As you may know the first day of a month was called a Calend and this of course gave us the word “calendar” as well as the sarcastical saying “to push a decision to the Greek Calends” which didn’t exist. Before the reform, only 4 months had 31 days and the 15th day of those months was called Ides[12]. Caesar didn’t changed this (he was actually murdered on the Ides of March, on March 15 of the year 44 BCE) but added days to other months to get the repartition of 30 or 31 days we know today, February being the only month remaining at 28.

To be exhaustive, I should add that the Romans also had a name for the day coming 8 days before the Ides because it illustrates an interesting detail about the way they were counting. The day was called Nones and was actually related to the number 9 because Romans were always counting the present day as the first day. As an example, when Caesar sent a message to Cleopatra saying “I should arrive in Alexandria in 2 days.” he actually meant “I’ll be there tomorrow”. This surprising way of inclusive counting has survived in many Roman languages. The French say “I’ll see you in 8 days” or “We’ll meet in 15 days” in lieu of 1 or 2 weeks. If Cervantes had written to Shakespeare “Nos vemos en una quincena.” (for an hypothetical meeting) the English would have had a hard time understanding why there should be 15 days in a fortnight, a word commonly used in anglosaxon countries.

Leap years exist because a solar year is actually about 365.25 days long.

One last thing added by Caesar was of course the leap day and because we happen to be in a leap year right now, let me say a few extra words about it. Of course, adding one day every four years is motivated by the fact that a solar year is actually about 365.25 days long. A 4 year cycle therefore has 1,461 days which are well accounted for by one year of 366 days and three years of 365 days. This day was added to February as it still is now but instead of being simply put at the end of the month, it was intercalated before February 24, a day which was named “ante diem sextum Kalendas Martias” because it was the 6th day before the first day of March. The extra day was therefore called the second sixth day (bis sextum) and explains the root for the word “bissextile”.

This constant necessity for the calendar to accurately match the exact length of the solar year is what will bring our last chapter in this story and finally explain our date problem. The leap day decision of Caesar was actually a solution as well as a problem. The reason is that the exact length of a solar year is not 365.25 days (or 365 days and 6 hours) as I wrote earlier but more precisely 365 days 5 hours 48 minutes and 46 seconds. In other words, adding one full day every four years was a bit too much, a little more than 11 minutes too much. To understand the consequence of this, let’s compare the situations before and after the Julian reform. Without the leap day, the calendar was getting behind by 5 hours 48 minutes and 46 seconds – a grand total of 20,926 seconds – every year. Since a year has 31,556,926 seconds the difference represents less than 0,1 % and one may consider this to be negligeable. However, after only a century the difference would amount to more than 24 days and, as explained before, the delay with the seasons would be noticeable. When Caesar was ruling, the Roman calendar had been in use for almost 700 years and this means it was way off with the observations, even though some adjustments had already ben made before. After the implemantation of the leap day, the calendar was ahead by 11 minutes and 14 seconds (or 674 seconds) a mistake which represents only about 0.002% of a full year. Astronomers of the time knew about this but because it led to a difference of less than a day after a century this seemed satisfactory.

Gregorian Calendar

Jump forward a millenium and the difference would be more than a week, something which may start to become noticeable again. Indeed, towards the end of the middle ages, scientists rediscovered the small discrepancy. One of them, the famous English philiosopher and Franciscan friar Roger Bacon wrote in his Opus Majus that the Julian Calendar was “intolerable, horrible and laughable” and advocated for a new reform. His work was sent to Pope Clement IV in 1267 but sadly the pope died the year after and nothing was done. This, and other historical facts including the Black Plague, explains why a change had to wait another century.

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the reform and gave his name to the Gregorian Calendar which is the calendar used by most countries today. Besides readjusting the date for the start of the Spring equinox (which in the late 1500’s was falling as early as March 10), the reform also wanted to correct the way the date of Easter was calculated[13]. In order to do this, two decisions were taken. First, the rule for leap days was slightly changed. It was decided that the last year of a century, despite being a multiple of 4, would not be a leap year except if it was also a multiple of 400. Following this new rule, the years 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not leap years but 1600 and 2000 were. And for those of you who are thinking that 2000 was not the last year of the 20th century but the first one of the 21st (and at the same time the first year of the 3rd millenium) let’s remember that the year 0 never existe and therefore the first hundred years of the Common Era were the years 1 to 100. As a consequence, the first century ended on December 31st of the year 100, the first millenium on December 31st of the year 1000 and the second millenium on December 31st of 2000. Thus, in a 400 years span (e.g. from 1601 to 2000) there would be only 97 leap days instead of 100 and this difference of 3 days corresponds almost exactly to the 11 minutes and 14 second that were gained every year.

Equinoxes and solstices.

Secondly, and most importantly as far as we are concerned here, to bring back the date of the Spring equinox to a more common March 20 or 21, 10 days had to be “removed”. This is exactly what happened during the year 1582. In Italy, Spain, Portugal and Poland, October 4 was followed by October 15. In France, King Henri III waited a couple of months and decided that the day after December 9 would be December 20. And because the reform had been implemented by the Pope many catholic countries (or catholic parts of countries) made the change before the end of the 16th century but protestant countries did not follow through right away. In England, after a failed attempt during the reign of Elizabeth I, the reform took place only in 1752. However, as I already mentioned, the year 1700 was a leap year in the Julian Calendar but not in the Gregorian one and, as a consequence, 11 days had to be removed : September 2 was followed by September 14. The change was valid in all British colonies, including the 13 thirteen colonies which became the Unites States. Other parts in North America had changed as early as 1582 because they were under French or Spanish rule. To conclude on that topic, let’s add that, for various reasons, some countries waited until the 20th century to adopt the new calendar. As an example, the Soviet Union had to drop the 13 first days of February 1918 when it finally abandoned the old Julian calendar.

There you have it ! Because Cervantes and Shakespeare died between 1582 and 1752 their deaths which were recorded as April 23, 1616 didn’t happen on the same day simply because England had not adopted the Gregorian calendar yet. In other words, the Spanish writer died 10 days before his English counterpart and, after all, this could be the reason why this “fact” didn’t make it to the bottle cap. Still, this “false coincidence” was remarkable enough to encourage the Unesco, in 1995, to choose April 23rd as the World Book an Copyright Day. What will you read (or reread) on that day ?

[1] Don’t you love those ? Here are a few favorites : Snapple Facts #69 – No word in the English language rhymes with month, #801 – You can’t tickle yourself, #866 – Abraham Lincoln was the tallest U.S. President at 6’4″. James Madison was the shortest at 5’4″, #79 – There are 119 grooves on the edge of a quarter or #921 – If you had 1 billion dollars and spent 1 thousand dollars a day it would take you 2749 years to spend it all

[2] This is Snapple Fact #301, although we actually only have a recorded entry for his baptism on April 26. Who would blame historians for assuming he was born 3 days before, if it makes for a nice story ?

[3] Our calendar means the Western (or Gregorian) Calendar which today is the most widely used in the world.

[4] Killed in 212 BCE by a Roman soldier during the siege of Syracuse while he was studying a driagram drawn in the sand.

[5] Before the Common Era or Before Christ as it used to be said. For the record, I owe most of the historical and technical details to the marvelous book “Mapping Time : the calendar and its history” by E.G. Richards.

[6] Four months had 31 days and the other six had 30.

[7] This is of course the reason why October shares the ethimological root with octopus despite being now the tenth month.

[8] Do you remember the three missing names ?

[9] 13 months would give 383.5 days and a bigger difference of 18.5.

[10] a number also very close to 6940 days

[11] The many intricacies of the Hebrew Calendar would require another story.

[12] It was the 13th day for the other months.

[13] This method called Computus necessitates various algorithms and also would certainly require another story.

About the Author :

Originally from Brittany, David Soquet graduated from the Université de Rennes, before becoming a math teacher. After honing his skills at a middle school near Paris, he joined the Lycée Français in 2008. He is the father of two children and is passionate about the history of science. In his teaching, he tries to balance the rigor required by mathematics with humor and discovery. He is very curious and his interests range from modular origami and norse mythology to Fritz Lang’s cinema and music.