Following a recent visit to the school robotics club, I have been thinking a lot about the concept of invention, particularly in the realm of technology. And whenever I have had a chance, I have been asking students questions like, “how do you think someone came up with the idea for the iPad”. Or “how did it ever dawn on someone to develop the first camera?” Or “how is it that someone managed to develop an engine strong enough to propel an airplane through the sky?” I do not know enough about the history of science to be able to answer most of these queries myself, but no matter.

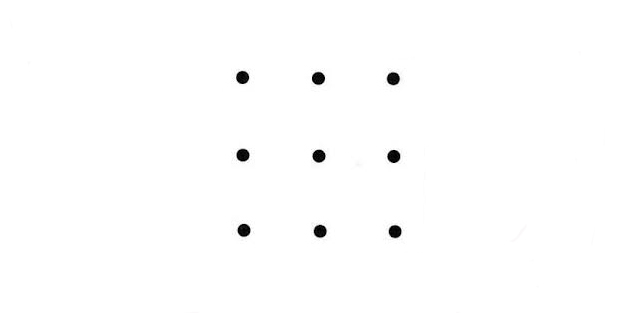

In my exploration of this theme, I have also been doing some research of my own and would like to share with you one the most compelling demonstrations about the nature of invention which I have so far been able to find, taken from The Art of Possibility by Rosamund Stone Zander and Benjamin Zander. Consider the following puzzle.

Your task is simple: “join all nine dots with four straight lines, without taking pen from paper.” Nb. if you do not wish to know the answer for the moment, and if only for the intellectual stimulation involved, please wait before reading the next few paragraphs. And have fun!

Think outside the box

The Zanders write, “If you have never played this game before, you will most likely find yourself struggling to solve the puzzle inside the space of the dots, as though the outer dots constituted the outer limits of the puzzle” (The Art of Possibility (New York: Penguin, 2000), p. 13). Indeed, the brain will always strive to recognize patterns and then to impose those perceived categories on the data it encounters. As Rosamund and Benjamin Zander remark: “Your brain instantly classifies the nine dots as a two-dimensional square. And there they rest, like nails in the coffin of any further possibility…nearly everybody hears: ‘Connect the dots with four straight lines without taking pen from paper, within the square formed by the outer dots’ (pp. 13-14).”

What interests me most about the above puzzle is to know what frames of mind might permit us to think outside of the box with which our cerebral functions wish to provide us. When faced with problems to solve, what can we do that will permit us to exploit the full powers of our intelligence and imagination? In the case of their enigma, the Zanders affirm, the secret is to think differently. “If we were to amend the original set of instructions [i.e. connect the dots with four straight lines without taking pen from paper] by adding the phrase, ‘Feel free to use the whole sheet of paper,’ it is likely a new possibility would suddenly appear to you (p. 14).”

More generally, they argue, what we can do when grappling with a puzzle is first to identify the assumptions we have for seeing the puzzle as we initially see it, and second to ask ourselves “what might [we] now invent, that [we] haven’t yet invented, that would give [us] other choices (p. 15).” Is that what they did, those inventors of the iPad, the camera and the jet engine, i.e. adopt an inventive frame of mind? Perceive that they could use the space around the proverbial nine-dotted square? Let me ask our students and get back to you with their thoughts.

About the Author :

Sean Lynch was Head of School at the Lycée Français de New York from 2011 to 2018, after having spent 15 years at another French bilingual school outside of Paris: the Lycée International de St. Germain-en-Laye. Holding both French and American nationalities, educated in France (Sciences Po Paris) and the United States (Yale), and as the proud husband of a French-American spouse and father of two French-American daughters, Sean Lynch has spent his entire professional and personal life at the junction between the languages, cultures and educational systems of France and the United States. In addition to being passionate about education, he loves everything related to the mountains, particularly the Parc National du Mercantour.