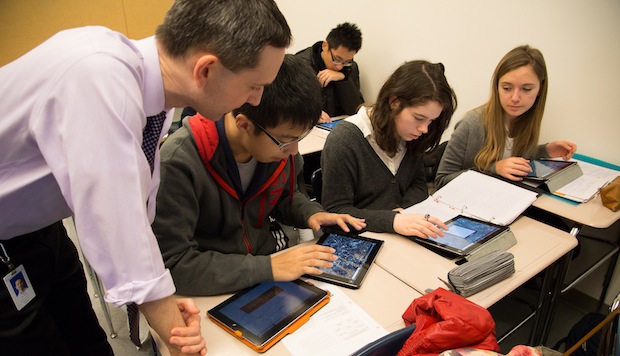

A Y10 Geography and Urbanism class at the Lycée Français de New York.

Q: How do you define school climate?

Dr. Jonathan Cohen: Practitioners have always suggested that school climate refers to the tone or atmosphere of school life. In 2007, The National School Climate Council (NSCC) developed the following definition synthesizing current thinking and research about school climate and culture: “School climate refers to the quality and character of school life. It is based on the patterns of people’s experiences of school life and reflects the norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching, learning, leadership practices and organizational structures that comprise school life.”

Q: How do you define a positive school climate?

JC: A sustainable, positive school climate is one that fosters healthy youth development (for example: in early adolescence, it is predictive of better psychological well-being) and learning necessary for a productive, contributing and satisfying life in a democratic society. It is an environment where:

– Norms, values and expectations that support people feeling socially, emotionally and physically safe.

– People are engaged and respected.

– Students, families and educators work together to develop, live and contribute to a shared school vision.

– Educators model and nurture attitudes that emphasize the benefits and satisfaction gained from learning.

– Each person contributes to the operations of the school and the care of the physical environment.

Q: Why is it important to foster a positive school climate?

JC: Research has shown that a climate where students and educators feel safe and engaged supports youth development and academic achievement. In schools absent supportive norms, structures, and relationships, students are more likely to experience violence, mental health troubles, “at-risk” behavior, often accompanied by high levels of absenteeism and reduced academic achievement.

Social climate comprises four areas:

– Interpersonal relationships, for example: How do we recognize and celebrate diversity? How well do students – and educators – feel supported? How connected or to what extent do students feel a sense of belonging with others? Do the social norms of a school support socially responsible engagement or passive acceptance of bad situations?

– Teaching and learning practices, for example: Do educators have high expectations for student success? To what extent do educators work to be social and emotional as well as

– Safety, for example: Do students feel safe: socially, emotionally and intellectually as well as physically? How consistently and fairly are school rules applied?

– Physical environment, such as overall cleanliness, aesthetics, suitable facilities and space, extracurricular options.

Q: Why is North America so aware of school climate?

JC: Educators here have been studying and writing about school climate for over one hundred years, but over the last decades, American schools have faced several major problems, as physical violence in schools, high dropout rates in high school (between 30% and 50 % in public schools), desertion of teacher posts (50% in the first five years from kindergarten to 12th grade in public schools).

But these are not just American problems. There is growing interest in school climate reform efforts around the world. And, our Center is working with educational ministries in Europe (including France), Asia and South-America as well!

Q: In France, we often consider that students have to remain “in their place” – seated and quiet. On the contrary, school climate promotes their participation and their involvement.

JC: It is certainly true that in France and many other parts of the world (including many schools in the U.S.) educators believe that teaching and learning is most effective when students are – literally and figuratively – “in their seats,” receiving information from the teacher.

There is a growing body of educational and developmental research suggesting that when students have opportunities to be more actively engaged and co-creators of learning projects, their academic achievement increases, and they are even more motivated to stay in school.

However, we believe that teachers need to be in charge of their classrooms – the classroom is not a democracy. But, educators don’t have to be harsh with the students. Research shows that children achieve academically at higher levels when teachers communicate in caring and supporting ways. Optimally, students know that their teachers have high expectations for them and will – in caring and appreciative ways – always tell them the truth about their strengths, weaknesses and needs.

It is curious that although we all have weaknesses, in America and abroad we do not talk about strengths, weaknesses and needs with students. This inadvertently can contribute to a sense of shame and an avoidance of asking questions when we “don’t know” and/or “feel confused” about how we’re doing. In fact, coming to terms with our strengths, weaknesses and needs provides an essential foundation for healthy development.

Q: What is the most important thing a school can do to improve its climate?

JC: Continually learn (through scientifically sound assessment) and work together to understand the strengths and needs of its existing school climate. School communities should work together to use this information to develop collaboratively instructional and/or school-wide implementation efforts.

To learn more about such efforts visit: www.schoolclimate.org

About Dr. Cohen

Jonathan Cohen, PhD, is also Adjunct Professor in Psychology and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University; and, a practicing clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. He has worked in and with K-12 schools for over thirty years in a variety of roles: as a teacher, program developer, school psychologist, consultant, psycho-educational diagnostician and mental health provider. He has authored over 60 articles, chapters and books. Dr. Cohen has consulted to scores of schools, districts and state Departments of Education interested in furthering social, emotional, ethical and academic education and positive school climate in America, France, Spain, Switzerland, Israel, Scandinavia, China and Peru.

About NSCC

The National School Climate Council is a group of policy and practice leaders who the Education Commission of the States and our Center convened to narrow the gap between school climate research on the one hand and policy, practice and teacher education on the other hand.

About the Author :

Professeure agrégée de Lettres Modernes et titulaire d’un Master professionnel de Psychologie clinique, Nathalie Anton a été membre pendant trois ans d’une équipe en charge de prévenir la violence en milieu scolaire dans l’académie de Paris. Elle est aussi l’auteur de l’ouvrage L’Art d’enseigner, paru aux éditions Ixelles en août 2012. Quand elle n’est pas en classe, Nathalie aime courir à Central Park et sillonner la ville à vélo l’été et se réchauffer dans les salles de spectacles l’hiver.