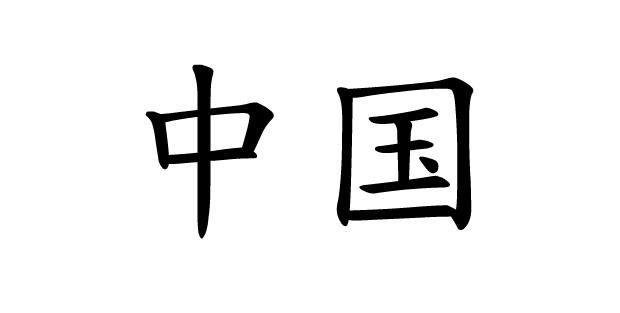

Chinese character for Love.

In any given year, the Lycée Français has some 400 students studying Mandarin, starting in CE2 when all of our third-graders are introduced to the Chinese language and continuing through twelfth grade when a quarter of our graduating class elects to sit the French Baccalaureate examinations in Mandarin. And the more our students study the Chinese language the more passionate they become about it. Time and time again, particularly among those who choose Mandarin as a third language in sixth grade, I have been struck by their answers to my deliberately innocent question: “Does Mandarin seem to be more difficult to learn than the other languages you know?”

“Yes, but” is the reply our students will almost invariably give: yes, mastering the Chinese language requires an enormous amount of effort, but the fruits of that work are also exceptional, because of the esthetic experience which the calligraphy of Mandarin entails and because of the extraordinary civilization which unfolds before them with every new character they learn. Each new character appears to have the capacity to transport them to another world, a world in which their minds feel like they are working differently from the way in which they do in other languages, a world whose cultural richness adds a dimension to their understanding of what it is to be human which would have been unattainable through any other means.

“Yes, but” is the reply our students will almost invariably give: yes, mastering the Chinese language requires an enormous amount of effort, but the fruits of that work are also exceptional, because of the esthetic experience which the calligraphy of Mandarin entails and because of the extraordinary civilization which unfolds before them with every new character they learn. Each new character appears to have the capacity to transport them to another world, a world in which their minds feel like they are working differently from the way in which they do in other languages, a world whose cultural richness adds a dimension to their understanding of what it is to be human which would have been unattainable through any other means.

Practice, practice, practice

“What advice would you give a beginning learner of Mandarin?” is my next query. To which the response is once more almost always the same. One of our students said as much to me just yesterday: practice, practice, practice. The teacher in me recalls the old educational adage which I only recently discovered comes from Confucius, namely that “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.” Not knowing the Chinese language myself, but trying to grasp as much as I possibly can about the teaching and learning of Mandarin, there appears to be something about the distinctive experience of speaking the Chinese language and the unique challenge of writing it which makes “doing” it, or to borrow the words of our students, practicing it especially invaluable to the process of “understanding” it.

“I do and I understand” reminds me as well of a wonderful book by Deborah Fallows entitled “Dreaming in Chinese: Mandarin, Lessons in Life, Love and Language” which I highly recommend to anyone interested in Mandarin, whether for themselves or their children. For Fallows, “there are tried-and-true ways to learn another language-be young, stick with consistent classes, immerse yourself in the speaking situation. But life doesn’t always work out in one of these ways, so you have to ad lib.”

“I do and I understand” reminds me as well of a wonderful book by Deborah Fallows entitled “Dreaming in Chinese: Mandarin, Lessons in Life, Love and Language” which I highly recommend to anyone interested in Mandarin, whether for themselves or their children. For Fallows, “there are tried-and-true ways to learn another language-be young, stick with consistent classes, immerse yourself in the speaking situation. But life doesn’t always work out in one of these ways, so you have to ad lib.”

“Dreaming in Chinese” tells the story of that “ad-libbing” or in Confucian terms the tale of how she “did” and in so doing how she “understood” something about the Chinese language and Chinese civilization during the three years in which she had the chance to live in China. By venturing out into the fascinating linguistic and cultural landscape of Mandarin, Fallows explains how she came to speak the Chinese language and to gain “at least the illusion that [she] belonged, if just for a little bit, in [that] extraordinary country.” May it be so for our own students too!

About the Author :

Sean Lynch was Head of School at the Lycée Français de New York from 2011 to 2018, after having spent 15 years at another French bilingual school outside of Paris: the Lycée International de St. Germain-en-Laye. Holding both French and American nationalities, educated in France (Sciences Po Paris) and the United States (Yale), and as the proud husband of a French-American spouse and father of two French-American daughters, Sean Lynch has spent his entire professional and personal life at the junction between the languages, cultures and educational systems of France and the United States. In addition to being passionate about education, he loves everything related to the mountains, particularly the Parc National du Mercantour.