On January 23rd, Ron Lieber, author and NYT Money columnist, published an article in The New York Times entitled “High School Grades Could Be Worth $100,000. Time to Tell Your Child?” in which he argues that a.) the current system of higher education aid rewards good grades with financial scholarships, and b.) parents should begin speaking to their children about these scholarships in eighth grade.

Since Mr. Lieber’s article, we have been thinking and talking together about when it is appropriate to begin discussing the financial implications of a college education. While both of us agree that encouraging families to display openness and transparency with their children when it comes to the cost of college, the timing and the tone of these conversations is not as clear.

We would argue that middle school is not the time to equate grades with money for college — especially not this year.

Middle school is a necessary time when low-stakes failure is welcome so that students can develop much needed coping skills. The pressure of merit-based aid is in direct conflict with this idea. Middle-schoolers are at a critical age for the development of their sense of purpose and sense of worth, and it is best to support who they are becoming.

Many middle-schoolers are not yet neurologically capable of the self-management and project-management skills required to achieve consistent academic success autonomously. Added pressure is likely not to change their performance, but rather to add to their stress levels. And, when students believe the stakes of their grades are too high, they are more likely to try to achieve high scores at all costs, meaning sacrificing their health and well-being, or perhaps even resorting to cheating.

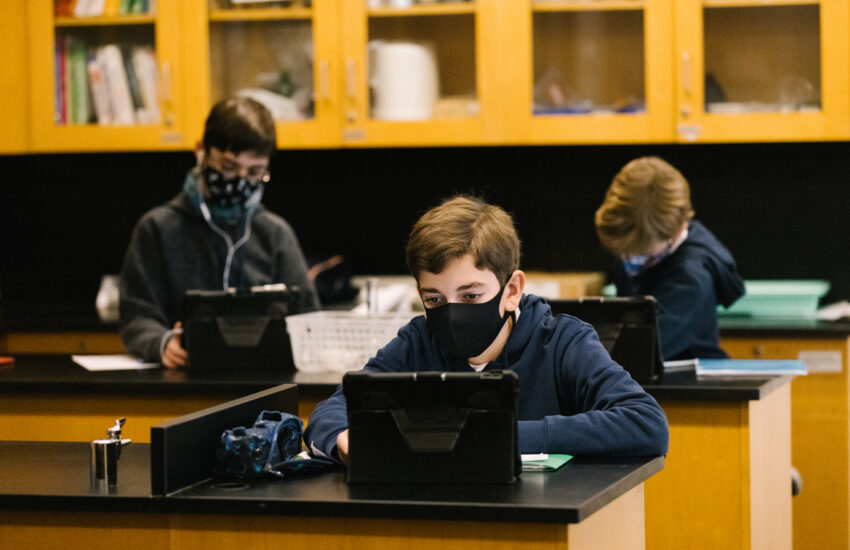

Given the intersection of multiple crises in the current moment, all students, and especially adolescents, face difficulties related to social isolation, a lack of perspective, and the loss of rituals and traditions. They are also aware of the financial implications of the pandemic, globally and locally – adding an additional layer of uncertainty.

Now is the moment to focus on our collective well-being, to celebrate the joyful moments and recognize what we have lost, to be thankful for what we have. Let’s remember that middle-schoolers are still children. They need to pursue their passions without concern for rewards; they need to spend time doing “nothing” (when the brain is actually doing quite a bit!), and they need the chance to enjoy being children.

The college application process in high school is filled with enough stress. Introducing its complexities to a 13 or 14 year-old may lead to unintended consequences.

As Denise Pope, senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education argues, “… some of these kids have had college on the brain since sixth or seventh grade or even earlier. When you have that kind of stress over that kind of time, that’s where it starts to worry us.”

So, when is the right time and what is the right way to start this conversation?

- Introduce college costs alongside the conversation surrounding financial literacy.; Connect them to organic opportunities that present themselves to discuss how families use and budget their money.

- During 10th grade, or their sophomore year in high school, things get real. Be sure to have honest conversations about college costs then.

- Take advantage of educational programming at the Lycée that introduces the vast array of global university choices, some of which are substantially less expensive than higher education in the United States. Many incredible options exist at all price points (some 3000+ of them), with opportunities for discounts.

- Once your child is in high school, families and students receive a weekly newsletter from the College Counseling Office with timely information and programs.

And as Professor Pope comments that despite all of the hurdles, “There is a college for every student who wants to go to college.” And, we fervently believe that leaving young teens the time to grow developmentally and intellectually will prepare them for the college application process and critical conversations around college costs.

Let’s not rush the process and jeopardize our kids’ mental health. That’s too high a price to pay.

About the Author :

Gail Berson comes to the Lycée with more than 35 years of experience in college admission and counseling. A magna cum laude graduate of Bowdoin College, she earned her master’s degree at Emerson College. She served as Vice President for Enrollment/Dean of Admission at Mount Holyoke and Wheaton Colleges, as Director of Admission at Mills College (CA), interim college counselor at Rocky Hill School (RI), and has consulted widely at a variety of colleges and independent schools. Gail, who has been a frequent speaker on college admission, is a former trustee of the College Board and currently volunteers for the World Leading Schools Association (WLSA) where she presented sessions at their summer programs in Shanghai, Jeju Island, Seoul and Prague. She also served as a past president of the Bowdoin Alumni Council. During vacations, she enjoys spending time with family and friends at her home on Nantucket.